Why Critical Chain is not a science - Part 1

Critical Chain is a revolutionary concept (introduced in the late 90s by Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt) in Project Management, that aims at plugging the holes in the traditional Critical Path method and providing a tangible mechanism for managing projects.

Over time, Critical Chain applications have produced tremendous performances in large, complex projects. There are many demonstrable results across the world to prove that it is a reliable method for delivering massive improvements in project delivery.

Yet, in spite of time and cost overruns in projects across the world, it is yet to be accepted as a mainstream solution.

This may be largely because of the many failures that have also happened. Whenever it fails, lack of expertise and/ or management buy-in/ understanding is/ are cited as the reason(s).

The reality is that even after 25 years of being in existence, Critical Chain is still not a science. The guaranteed benefits are still not repeatable and reproducible in project after project.

We need special people to do it, people who are able to interpret the solution elements ‘in the right way’. It is still an art that only a privileged few can understand. This is a major deterrent to wholesale adoption across the world.

In this series, we will attempt to question the ambiguities encountered in Critical Chain and try to find answers from within and outside.

Part 1

Let’s consider the following example:

A work front for constructing 100 civil foundations are available. Each foundation requires a resource team of 4 people – 1 bar-bender, 1 carpenter and 2 Riggers. Unfortunately, only 10 such teams could be mobilized at site. The pressure to complete the foundation works is high.

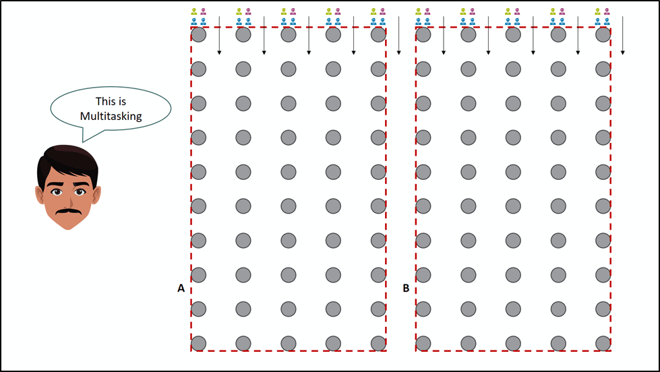

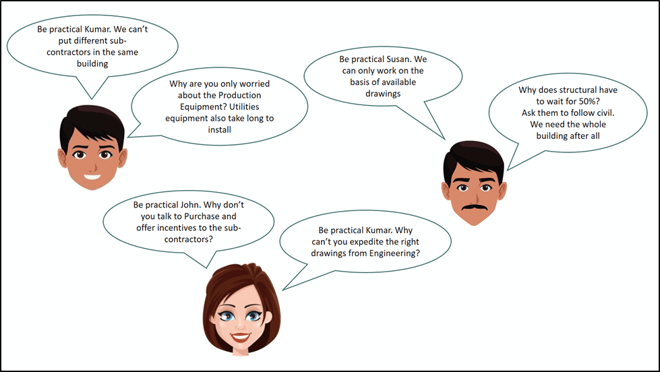

John knows that multitasking is bad.

Theoretically, he can try and start 40 foundations and coordinate the resources meticulously to get continuous progress on all of them.

Alternately, he can maintain a Low Work-In-Progress (WIP) and focus the teams on 10 foundations (and not worry even if the members go idle from time to time).

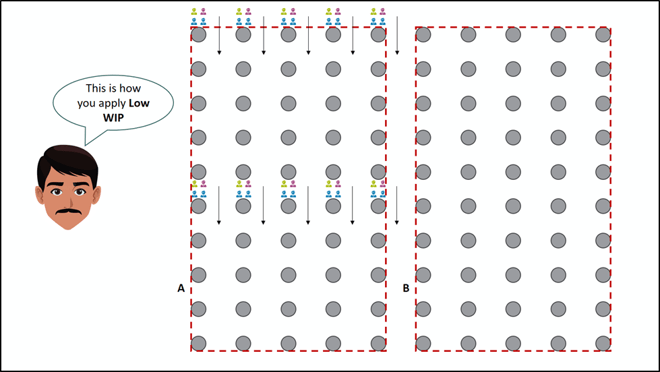

Kumar knows multitasking is bad. And he thinks John is promoting multitasking.

Because the 100 foundations are from 2 buildings – A and B – he thinks it will only be Low WIP if they are concentrated on 10 of the 50 foundations from Building A. Production equipment will eventually be installed in Building A and hence, it needs to be prioritized over B (B will house Utilities)

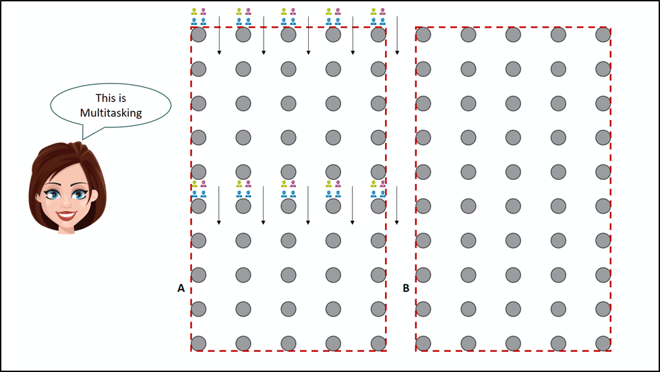

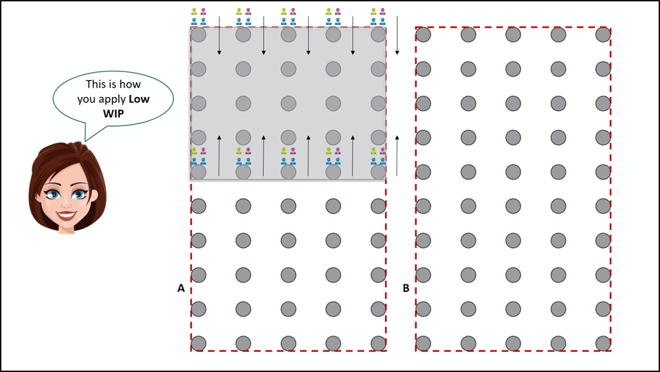

Susan knows multitasking is bad. And she thinks both John and Kumar are promoting multitasking.

Because half the foundations from one side of Building A needs to be handed over to the structural erection team, she thinks it will only be Low WIP if they are concentrated on 10 of the 25 foundations from Building B.

The Multitasking and Low WIP paradox

At the heart of Critical Chain methodology, lies the concept of multitasking that ostensibly solves the resource limitation problem in projects.

Unfortunately, even after 25 years, this central tenet remains a ‘philosophy’ that only a handful around the world has been able to master.

All three are talking the same language but suggesting different actions. Which one is the correct interpretation?

- John

- Kumar

- Susan

- Need more information

- None of the above

Find this article interesting? Watch this space for Part 2

.png?width=642&height=150&name=Logo%20(1).png)